History on Italian small screens and on the Web, May 2017

Second update

Updates

2012 (tv) | 2014 (web) | 2016 (web) | 2016 (tv) | 2017 | 2018

by Gisella Gaspari

History had an important place in Italian television programs during the 20th century. At the time the memory of World wars and of the Cold war was much alive, people were eager to get a comprehensive view of troubled years they had experienced without understanding clearly what was going on. RAI [1], the Italian public television, which benefited by a monopoly of broadcasting till 1980, considering it a duty to strengthen unity between Italians by helping them to think over the past of their country, put on the air important, carefully prepared series about the world conflict, fascism and the decades of terrorism that had bathed the peninsula in blood.

Commercial channels, once they were allowed to freely transmit, challenged RAI on this ground, Rete 4 (Network 4), member of Mediaset – the group owned by Berlusconi – launched Appointment with history (Appuntamenti colla storia, 1996-2008) while LA7, independent channel, set in motion Another history (L’altra storia, 2002-2007). RAI replied with spectacular transmissions, The Great History, (La grande storia, 1997-2016) spectacular exploration of the 20th century and short, alive chronicles of the past, We are history (La storia siamo noi 1997-2010). The same network opened also the 2 Febbruary 2009 a channel entirely dedicated to former times, RAI History (RAI Storia). When the 21th century began, older days figured largely on Italian small screens.

History as it must be told

In the 2010s the panorama has radically changed. Commercial networks have abandoned history, only LA7, in his encyclopedic series Atlantide, offers, inserted between broadcasts on geography, botanic or anthropology, a glance at a past epoch [2]. RAI Storia recycles old transmissions, notably, everyday in the afternoon, One thousand Remembrance Poppies [3] (Mille papaveri rossi) a series about the conflicts, wars, crisis and tragedies of the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as Civic Calendar (Diario Civile), biographies of people that fought for justice and the respect of law. RAI 1 broadcasts, in the morning, Italians, biographies of Italians who played an outstanding part in the social, political or religious life of Italy, a program later replayed on RAI Storia. The most interesting and original transmissions are televised on RAI 3: every day at 1.15 p.m. Time and History (Il tempo e la storia) analyses, with cinematic illustrations and the comments of historians, a situation, a problem or an event of the past; every Saturday, at 9. 15 p.m., Ulysses (Ulisse), a two and half hour program, gives a wide-ranging panorama of a bygone period.

The noticeable diminution of history programs confronts us with a problem. It is, to a certain extent, the result of an evolution in the conception of history by professional historians. The 5 May RAI 3 aired, in its Time and History series, 1917, the Crisis of Germania. Most viewers associate 1917 with the Russian revolution, the end of war on the eastern front and the military intervention of the USA. The broadcast showed the intricacies of a state of affairs that implied conflicting political forces, contrasting military options and the claims of civilians caught between patriotism and exhaustion. The year 1917, it was told, did not boil down to events that had occurred in foreign countries and battles. Spectators, not finding in this broadcast the happenings they expected, felt disconcerted; the subtlety of the analysis exceeded their competence and, contrary to the custom, few opinions (only five), reduced to a prudent “I like”, were expressed on the site of the broadcast.

Germany 1917, a starving population has lost its confidence in victory, its exhaustion weighs heavily on the running of war.

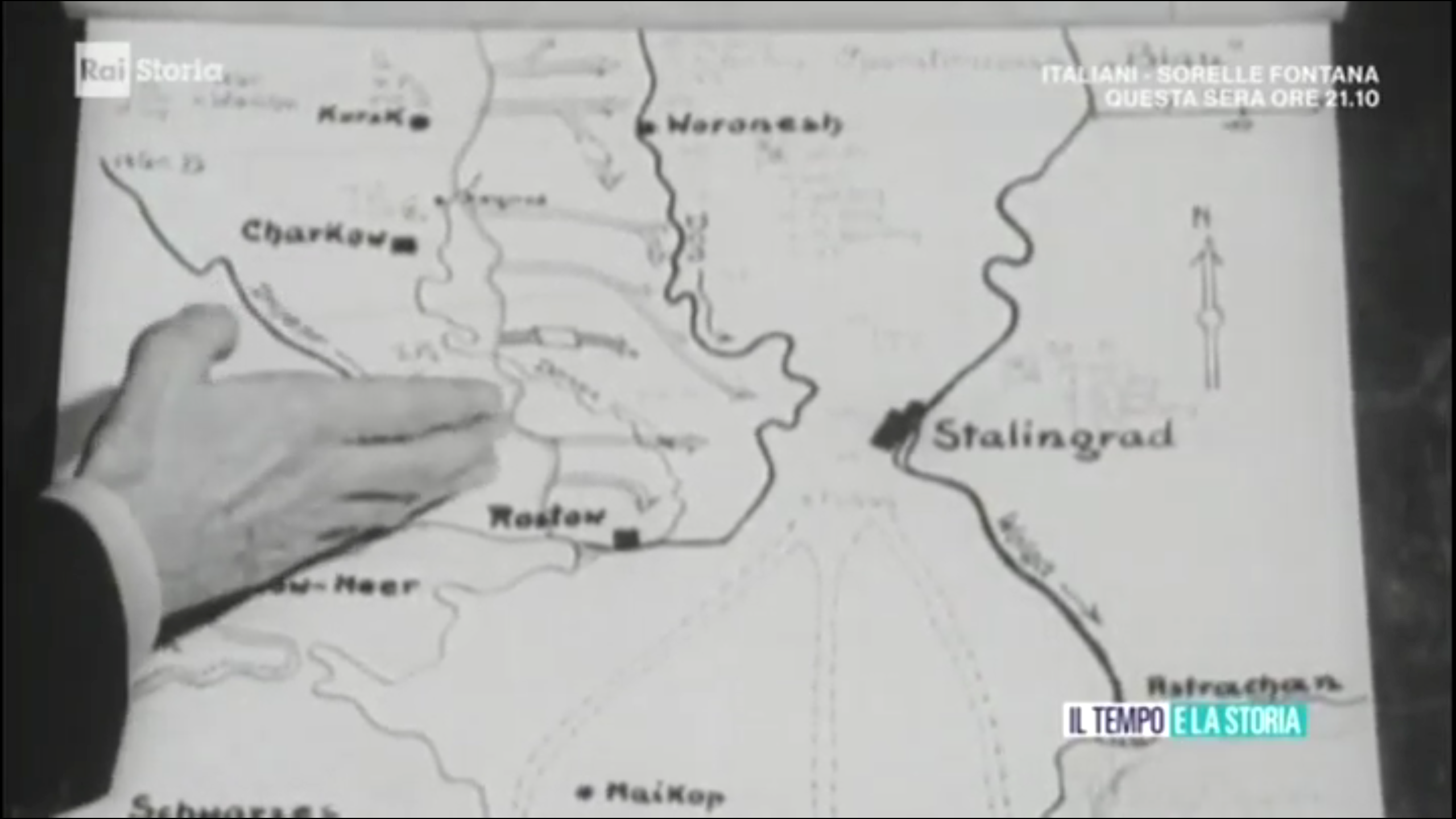

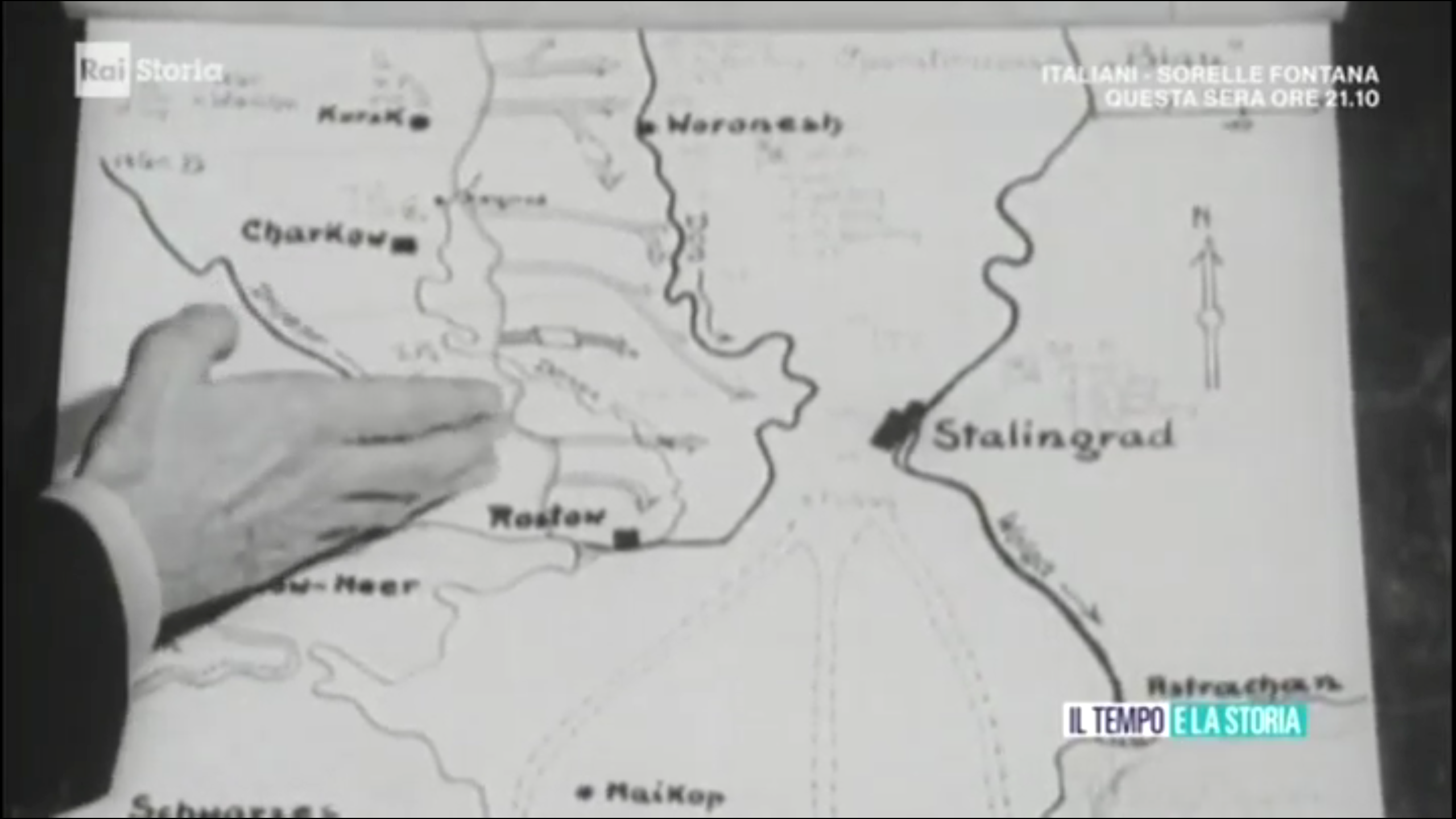

We broach here the main reason of the changes mentioned above; television is no longer a top bottom medium that inflicts an unquestionable discourse on its public, the viewers make themselves heard on the Web, criticize, express their preferences and the channels adapt to the dominant requests. People prefer well-structured stories: a predicament, the attempts to overcome it, a solution and, if possible, a positive one. On May 2d, Time and History put on the air The Battle of Stalingrad. Initial situation: the Germans besiege the city, a perfectly clear map locates the opposed forces. Central episode: the Soviets summon up their best troops and prepare the counterattack. Climax: the Wehrmacht, assailed from all directions, surrenders. The film was a great success; messages were flowing onto the site of the broadcast, viewers debated passionately: was it the turning point of WWII? The battle

A clear map that makes the battle of Stalingrad easily comprehensible.

that brought the German army to its knees? One of the best encircling movements in military history? An identic scheme is systematically applied in the innovative RAI series The Great War, a hundred years afterwards that, avoiding the unimaginative chronology, airs from 2015 (Italy entered the war in 1915) to 2018, thematic films (Writing in War, Hunger in War, The Military Justice, Women in War …) that meet with an excellent reception.

Straightforwardness does not mean narrow-mindedness or chauvinism, provided that the narration be easily comprehensible, the audience admits unconventional opinions. In October 1917 Italy suffered its worse defeat, 40,000 men were killed, 250,000 taken prisoners. The Caporetto disaster [4], usually quickly called up in history books, is the topic more widely developed in The Great War. The account is classically organized: Why the Italian army, although superior in number, was vulnerable in the autumn of 1917. How the Austro-Hungarians, in ten days, conquered the main part of Venetia. What the consequences of the disaster were. However, instead of lingering on military actions, the four episodes dedicated to the event emphasize the errors of the command, the inadequacy of the means of communications, the fact that, giving greater place to offensive, the staff had no plan for a well-ordered retreat so that the initial withdrawal quickly turned to rout. In addition, much place is devoted to the forgotten of any war, the civilians, persecuted and exploited by the occupiers or, when they had run away, unwelcome in the southern provinces of Italy. Under the watchful gaze of their spectators television channels prove keen on going beyond the mere enumeration of facts and offering their public something to think about.

Civilians: the forgotten of any war. 400,000 Italians fled from Venetia to escape the Austrian occupation that was

The profit of a simultaneous study of television programmes and of their echo on social networks is that it shows how spectators reacted to the images and how their answer influenced the channels in the making of other transmissions. The filmmakers of The Battle of Stalingrad wanted it to be seen in the general context of WW II in which it was a turning point, the broadcast did not linger on the enormous human price that both the Red Army and the Wehrmacht had to pay and the comments on the Web were extremely rational, some deplored human losses but in a lucid, almost cold way.

On the other hand the programme on Caporetto, in which casualties, destitution, fear were emphasized provoked, among the viewers, strong emotional reactions. The debate began with logical, sound queries: who had been responsible for the disaster, the commander-in-chief, Cadorna, who had not counted on an Austrian blitz or his seconds in command who reacted belatedly and weakly? Hundreds of Italian soldiers had been killed, why the culprits, and first of all Cadorna, were not put on trial and punished? The discussion, shifting from facts – why? – to moral questions, gave rise to a polemical reply: because, in Italy, there is a permanent complicity between those who hold the power, the same collusion operated in the 2008 crisis, when the State saved the banks at the expense of ordinary citizens. The moving of feelings manifest in the last statement triggered off immediate counter-attacks, which evidenced that the memory of Caporetto implied much more than the mere record of a battle, insults burst forth: “Illness has impaired your mental faculties”, “You, stupid ass, you know nothing about history”. Italy, whatever its rulers, has always been able to overcome hardship, “I am proud to be Italian, notwithstanding difficulties our country will never die”. Such declaration of love for one’s country is worth noticing, the television presentation of Caporetto had shaken the national pride of many spectators, the discussion opened onto a recurring problem: is there an Italian nation? Was unification, as it occurred in the 19th century the union of people who wanted to live together or a political operation, which subjected the South of the peninsula to the North?

We have summarized the very harsh controversies induced by a history transmission that implied tens of Web surfers and demonstrated how some broadcasts were likely to occasion hot-headed controversies. Television networks are aware of the risk; an arguable presentation arouses interest and curiosity but may endanger the credit of the channel. It is not by chance that, as we shall see soon, history programmes avoid disputable issues and prefer topics that please everybody.

History was long the written relation of past events. The addition of inanimate paintings or photographs made the narration more diverting but did not put right the paradox of historical accounts which transcribe in words, that are mere abstractions, human actions that are life. The audiovisual media, cinema, television, light video, digital recording have modified the state of affairs. Moving images introduce, in our relationship with the past duration and emotion, two dimensions of life that sentences have trouble expressing. On a screen, whatever its dimension, we observe the image of people acting or suffering throughout time, there is no possible comparison between a text relating the opening of the death camps in 1945 and the films shot by the Allies, our awareness of what horror the Shoah was is inseparable from the pictures taken then. Cinema and television were able to make their public feel enthusiasm, compassion, grief and to show how the passing of years affected people, landscapes, natural or constructed sites but, in front of these media, audiences receive messages passively. With digital implements everyone can record, edit, diffuse, so that amateur films circulate in hundreds on the Web and are often projected on television. Since the last third of the 2Oth century a huge archive has formed, where all kinds of businesses and happenings, trivial or important, individual or collective, are equally kept. We know little about the daily routines of countrymen, shopkeepers, linen maids and porters in the 16th or the 17th centuries but, thanks to the pictures accumulated in the Cloud by our contemporaries, we would be able to reconstruct hour by hour the life of any individual. Interfering in tv channels by its messages and its videos, the public influences the presentation of history.

These good old days that vanished too fast.

From an institutional point of view the difference between television networks and social networks is evident but the distance is less clear, sometimes even scarcely discernible where private lives are concerned, opinions, judgments and requests emitted by Web surfers influence the television channels, whereas the tv networks, by trotting out news broadcasts five decades old, invite their viewers to go back to their youth: television is, to a large extent, a nostalgia machine. As we have noted, RAI Storia reuses abundantly old programs that spectators see again, twenty of thirty years later, with much pleasure. The same channel puts also in the air original compilations that conjure up past periods. The sketch bellow shows, in red lines, how much time is consecrated to nostalgia transmissions on RAI Storia during any weekday:![]()

No less than four transmissions, It Happened Today (Accadde oggi), This Day and History (Il giorno e la storia), The Way we were (Come eravamo), Yesterday and Today (Ieri e oggi), We are History (La storia siamo noi) lure the public of RAI Storia into olden days. RAI 1 airs, on Wednesday morning, Your Year (Il tuo anno) and, in the evening, The Best Years, two hours and a half of music composed between the 1960s and the 1990s while, the same evening, RAI 2 broadcasts Histories. The Tales of the Week, a mix of events, which happened in past years during the same week and of facts that have just occurred. These transmissions are not redundant; they come up to different expectations.

Your Year, This Day and History, It Happened Today count on the pleasure of bringing past circumstances back to life and judging them with detachment. The former, focusing on the 1960s, the adolescent years of people who are now about to retire, recalls happenings (The Berlin wall, Kennedy’s murder, the 1960 student rebellion) that marked the decade [5]. This Day and History presents newsreels or tv news bulletins such as they had been screened in their epoch, without any additional commentary; take as an example the 4th of May: 1932, Al Capone put in jail, 1949, the death of the whole Turin football team in a plane crash, 1979, interview of Margaret Thatcher about the situation in Lebanon, 1980, death of Marshal Tito. Much more elaborated, It Happened Today alternates old occurrences and recent facts, well illustrated items and carefully commented affairs: always on the 4th of May the arrest of Gandhi by the British police (1930) is followed by the arrival of Margaret Thatcher to the ten of Downing street (1979), the first human flight in a Montgolfier (1783) by the electoral victory of Solidarność in Poland (1989); comments on Montgolfier and Gandhi are brief, but the pictures (coloured drawings for the former, diversified views of India in the latter) are excellent, precise; relevant texts summarise Thatcher’s political career and the evolution of Poland in the 1980s, while the images are wearisome. We were History is an enlarged version (one hour instead of 20 minutes) of Your Year. On May 11, the broadcast skimmed over the year 1911, “Holy Year of the Homeland”, in which Italy had celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of its unity; the first half of the program listed the progress made in fifty years and recalled the festivities that had marked the jubilee, the second half was a succession of short sequences dealing with events that had occurred then.

The Way we were and Yesterday and Today are fairly different from the programs mentioned above, both put in the air amateur films shot in super 8 or in video. The former imposes a topic such as, on May 1st, The Way we were young, 1958-1962; whatever their technical quality, the films sent by spectators that seem more “representative” (a ill-defined notion that gives free hand to those in charge of the program) are broadcast without comments (no place, date, individual names) but with a music of the period.

“Summer holiday picnic in the 1960s”. On Facebook a viewer comments: “Those filmed here were all born before or during the war and had been subjected to the hardships of war. For them the material well-being of the 1960s was like paradise”.

In Yesterday and Today people choose freely their subject matter provided there be a comparison between a past epoch and the present. The diversity of solutions make the program extremely attractive; some, starting from an old document, film the same areas, which have changed along the years, others ask a young person to comment, from their point of view, a film shot forty years before, while others play on the contrasting ways of filming yesterday and today. The transmission is popular, to take but an example there were, on the Web, a hundred and eleven messages about School yesterday/School today, with harsh debates: elementary teaching has it improved or declined in the past decades? These programs, relatively brief, deprived of narrative continuity, don’t require careful attention, spectators can chatter while watching them, their talks, spontaneous, desultory, are then echoed in short dialogues and funny exclamations on Facebook.

Less superficial and requiring an effort of concentration two other broadcasts, Italians, and Ulysses, focus also on foregone periods. Italians, a fifty-minute, carefully prepared program, puts the emphasis on individuals that have enhanced the image of Italy in foreign countries. The personalities celebrated at the beginning of May were Pope Paul VI, the three Fontana sisters and Susanna Agnelli. The latter, minister of Foreign Affairs, championed vigorously the Italian position in the United Nations. The Fontana sisters, head of a leading fashion house patronised by cinema stars and American First Ladies, diffused abroad, especially in the USA, the Italian “Haute couture”. Paul VI, a daring Pope reveals the ambiguities of this series, the man was neither an outstanding priest nor, later, an exceptional bishop of Milan and the program, besides marks of clerical reverence, dwells mostly on his journeys throughout the world once he was on the papal throne; he was the first globe-trotter pope – but, when he covered the whole globe to meet the faithful, did he appear as an Italian citizen or as the leader of the Roman Catholic church [6]?

Ulysses, an ambitious two and a half hour transmission, explores in deep a topic, sometimes geographical or scientific, but most of the time historical. We shall take into account two programs, A trip in the Name of the Rose (Viaggio nel nome della rosa) and A trip in the world of Mona Lisa (Viaggio nel mondo della Gioconda) [7]. Both films raise a question and apply to answer it: What life was like in the epoch where Umberto Eco set his world-famous novel, The Name of the Rose? What is the place of Mona Lisa in Leonardo da Vinci’s work and in the Italian Renaissance art? Answers are given slowly, in a roundabout way, with pleasantly filmed digressions on landscapes, old houses, rare plants and monuments. The program on Eco’s book combines cleverly sequences of the film adapted from the novel, medieval images and pictures shot in the still active Subiaco monastery, where the fictional story takes place. Such resources were not available for Leonardo; the filmmakers clumsily replaced them with actors who had the part of Leonardo, of his friends and of great figures of the period.

Leonardo himself! The actor prudently avoids putting his pencil on the canvas.

Viewers do not disapprove that kind of naïve reconstitution in transmissions that, like Italians, pay homage to Italian glorious periods; the Web commentaries dwell on that aspect, “Congratulations! I would now appreciate an entire series dedicated to the great masters of science, art, literature that Italy has given”. All programs, in Ulysses, portray a clean, fresh world. Free from dirt, illness, starvation, the screened past is inhabited by good-looking individuals, wearing laundered clothes and by well-fed animals. The public appreciates a reassuring universe, much brighter and safer than the ugly, alarming present. It could be objected that television history consecrates much space to wars, but, as we have noted, these days the doom of civilians, previously ignored, is widely taken into account.

The Web messages commenting nostalgia programs are unequivocal: “Thanks to RAI Storia we can admire an Italy which enjoyed style, elegance that, unfortunately, we no longer have”, “Wonderful times, few simple things that gratified us, we did not desire much and were happy, whereas today…”, “The 1960s, what an epoch!”, “Where is, today, the fellow-feeling of that times?”. The tweet of a lady encapsulates perfectly the sensitivity of those who watch history programs, as well as the significance of their longing for these good old days: “I understood that I was ageing when I realised that I couldn’t wait the Saturday evening because there was Ulysses on television”. An elderly confesses that, since Ulysses is broadcast, he knows what to do on Saturday evenings. Viewers are carried to another planet where grass is green, flowers in full bloom and difficulties easily solved. RAI Storia: for many, especially for old people, a daydream of fancied, embellished former times.

The burden of the past.

The first week of May had been chosen for our common inquiry about the representation of history because at that date the Labour Day is celebrated all around the world and because, on the 1st May 2004, ten East European countries officially adhered to the European Union that passed from fifteen to twenty-five members. There is no trace of the last event, not even an allusion, in Italian television programs, the only European anniversary accurately celebrated had been, the 24 March, the signature of the Rome treaty in 1957. The 1st May, most television channels recalled, in a grave, preoccupied, not to say pessimistic tone, the symbolic purpose of a holiday dedicated to labour and to the labourers. However, the historical survey of previous celebrations of the Labour Day aired by RAI Storia did not allude to the international character of a feast that should yet emphasize what units all proletarians, whatever their country. In the margin of a transmission, a blogger noted: “The 1st May is becoming the feast of the memory of labour”. Another mocked Good First of May, a famous painting, and icon of the Italian Labour movement. On the canvas [8] three workers, two men and a woman carrying a baby march proudly, followed, in the background, by a dense crowd of workers; the facetious forger substituted the crowd with the shelves of a supermarket with the result that the three main characters seem to be looking for some can of food.

The 1st May 2017 the celebration of work was overshadowed, in Italy, by the recollection of a blood bath that, seventy years earlier, had dragged the South of the country in a spiral of political crimes. Before their landing in Sicily (July 1943) the Allies had negotiated with local gangs, which guided the soldiers and helped to drive the Germans from the island. The situation was then rather chaotic, armed bands, engaged in weapons, food and tobacco dealings, challenged the feeble government and supported those who championed the independence of Sicily. A few groups continued their illegal activities after the end of the war. In the island latifondi (large landed estates let lie fallow) occupied one third of the cultivable land.. After the proclamation of the republic, the countrymen, supported by the communist party, claimed a share-out of the leftover pieces of land. The 1st May 1947 two thousand people, farmers and their family, gathered at Portella della Ginestra, small village in the province of Palermo, to voice solemnly their demands. Soon a shooting brook out, eleven individuals among whom four children, were killed, twenty-nine seriously injured. Later the premises of the communist party were bombed in several towns. Only one gang lead by the young Salvatore Giuliano (he was only twenty five years old) had enough machine-guns and bombs to commit such attacks. Hypotheses mushroomed: had he been paid by landlords who did not want to part with their land? or by the Italian right (in contact with the Home Office?) to weaken the communist party? or by the Americans who had designs on Sicily? The police were looking for Giuliano, but he was murdered by one of his men who, in turn, was poisoned so that there was no proof that Giuliano had been manipulated.

The gun-fire is beginning, people try to escape. Screenshot taken from the film Salvatore Giuliano reused in the program broadcast on RAI 3.

The Portella massacre ran right through the television broadcasts and the Web chats during the first week of May 2017. The 1st May it was amply mentioned during the official ceremony transmitted by RAI 1. In the afternoon RAI 3 broadcast in full the commemoration that was taking place on the very site of the slaughter. Two historical accounts were presented respectively on RAI Storia and, in a more innovative way, on RAI 3. Country people, in 1947, were not used to taking photographs, there are visual documents neither on the meeting nor on the shooting and the few eyewitnesses, in their childhood at the time, have a dim recollection of the drama. A feature film, Salvatore Giuliano, was shot in 1962, under the direction of Francesco Rosi, the staging of the attack is outstanding but brief because the fire did not last long and because echoing such a tragedy is always risky. and this work was soberly exploited on television. The program exploited the film soberly and focused on the ambivalent situation of the post-war Sicily, cut of from the continent from its liberation to the end of the conflict, toying with the idea of secession, upset by the rivalries between gangs and by social unrest.

The historical context analysed in the broadcast accounts, at least partially, for the recourse to an anonymous, blind violence but who did unleash such wildness? The transmission cautiously avoids a question that haunts public opinion [9]. During the remembrance service, at Portella, all speakers had insisted that it was urgent to open the military and police archives where the documents on the massacre have been classified as ultra secret. On the Web, the bloggers expressed forcefully the same wish: “Italy wants to know the truth about all attempts. A democracy cannot survive with secrets kept hidden by the authorities”. Conjectures flourished, Giuliano had served as the instrument of the mafia – no, he had rather been “the military wing of the separatists” – or he had “put into practice Truman’s doctrine”. Regardless of their divergences the Web surfers agreed on the fact that, with “the first State murder” the Italian republic had entered seven decades of political injuries and damages.

The public television proved aware of such preoccupation. To show that the Portella slaughter had opened the way to a systematic recourse to criminal terrorism, RAI Storia aired throughout May, in its Civic Calendar series, a good many documentaries about bloodsheds that had shacked Sicily [10]. We shall be content with mentioning the murder of Pietro Scaglione, State Prosecutor in Palermo (5 May 1971), of Boris Giuliano, Chief Superintendent in Palermo (21 July 1979) and of Pio La Torre, Sicilian M.P. (30 April 1982) three programs broadcast the 2 and 3 May. Scaglione was called “the first victim”. Previously criminal groups had killed rival traffickers or individuals who did not want to give them money but they had never aimed at a government official. The State Prosecutor had inquired about Portella della Ginestra and other illicit business but, in the absence of legislation against a delinquency based on nuclear families networks, he had got no results. In June the magistrate should be transferred to the continent, the documentary makes it clear that his murder was nothing but a challenge addressed to the authorities: “We kill where and when we want”.

The police got the message. The film dedicated to Boris Giuliano portrays an officer aware of the changes that have taken place in organized crime: illegal activities have been divided between the different groups which no longer fight each other and infiltrate local administration to profit from public invitations to tender. Inquiring into kidnapping, drug traffic, tax evasion, Giuliano threatened many people who united to pay a killer. The construction business was an activity especially beneficial for speculators: on the pretext of clearing slums in big cities they evicted the inhabitants; with the complicity of the town hall they received subsidies and constructed rich-looking buildings sold to affluent people. As emerges from the documentary about his combat, Pio La Torre fought corrupt practices in Sicily where he denounced openly the crooks, and in Parliament where he prepared laws against criminal activities. His murderer has never been identified.

Pio La Torre lead careful inquiries in the poor Palermo districts to avert fraudulent evictions and demolitions. He didn’t take precautions so that it was easy to kill him.

The broadcasts on assassinations, misdeeds and bribery in Sicily gave rise to extended commentaries on the social networks. If there was nothing new or surprising in these programs their quick succession evidenced the strength and endurance o enterprises that defied the Italian State and its codes but found in the island a favourable ground. While approving of decision taken by RAI Storia to lay stress on the question, the bloggers hinted at circumstances too speedily mentioned in the transmissions: Scaglione’s role in the inquiries about the strange death of Enrico Mattei, head of the National Petrol Cy or La Torre’s campaign against the installation of an American nuclear base in southern Sicily were not at the origin of their elimination? – but nobody asked for a program getting to the bottom of things and analysing the roots of an underground, or parallel society in Sicily. It seems that, in the mind of the Web surfers, the Sicilian case, legacy of the past escaped as such any form of explanation.

What for History?

History programs have a large audience in Italy, Ulysses, despite its length, attracts every Saturday night ten per cent of the public. The tweets on Facebook as well as on the sites of the transmissions confirm such active concern. The debates, sustained and sometimes very rough, are often loosely connected with the subject of the transmissions and reflect mostly the preoccupations of the bloggers. A broadcast of Time and History dealing with the poorest outskirts of Rome in the 1950s [11] gave way to a surrealist discussion about children prostitution in which a forumer resorted to the testimony of Oscar Wilde and was called “stupid ass” by his adversary. Mysterious developments lead the dialogue on Portella della Ginestra to a furious polemic about Berlusconi and the political movement Cinque Stelle. The discrepancy between an interest in the programs and a permanent tendency to dispute about other issues requires some explication.

History is not merely a chronicle of past days; it implies also an interpretation of the relationship between yesterday and today. According to the perspective he has chosen the historian offers models or lessons that could be applied in the present and signals solutions that should be avoided, or illuminates the origins of the contemporary problems, or advances examples, which will help to understand the mechanisms of human decisions and actions, or situates one’s generation in the continuity of times. Italian television history offers another point of view, a dual vision of the country’s yesterdays. On the one hand, it shows that a form of permanent transgression has emerged and flourishes in Sicily; such inheritance, that goes back many decades, weighs a lot but what could be done to get rid of it? On the other hand, in contrast to the not very heartening events now occurring, history programs help forget on going worries by returning to the days of yore.

The popularity of history transmissions does not allow us to come to believe that Italian spectators indulge in a resigned nostalgia, their passionate controversies on the social networks prove that they use past situations as arguments to contend about up-to-date issues. The Italian television history is resolutely a glance at vanished periods and cannot serve to interpret the present-day world. As we have seen it deals chiefly with the 20th century: which lesson could be drawn from world conflicts that opposed national armies in a time when “asymmetric wars” oppose regular armies to polymorph, stateless, irregular groups that merge into the population? History broadcasts are entertaining because they bring universes different from ours back to life.

Notes:

[1] R.A.I. = Radio Audizioni Italiane (Italian Radio Listening). The historical acronym has been conserved with the addition of: TV.

[2] We have not taken into account HD History and the National Geographic, which broadcast exclusively foreign, mostly American programs.

[3] Reference to the poppies that, growing on a former battle-field, recall to the living those who were killed there.

[4] The chaotic retreat of the Italian army is described in the penultimate chapter of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929)

[5] The series i salso avaible in DVD. It has been so successful that another series of DVD, using newsreels, has been consecrated to the 1950s.

[6] The program doesn’t even mention his most famous, and most debated encyclical letter on sexuality, Humanæ vitæ (1968).

[7] Both broadcast at the end of April, the program put in the air during the first week of May dealt with the rehabilitation of monuments destroyed by earthquakes.

[8] Painted by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo in 1901.

[9] Note that Rosi’s film doesn’t tackle the question. It mixes up cleverly the different points of view of the local police, the continental journalists, the central authorities and the Court that judged the affair after Giuliano had been killed.

[10] Most murders of politicians or magistrates were committed in May notably those of Pietro Scaglione and Pio La Torre mentioned here, those of the judge Falcone and the civic militant Pepino Impastato.

[11] “Ragazzi di vita, il romanzo delle borgate” (The Ragazzi), 3 May 2017. This program, based on Pasolini’s novel Ragazzi di vita,described the wretched life or neglected children in the outskirts of Rome.