Abstract

The Second World War represented a very difficult time for the whole of Europe regarding food supply and the civil population in many areas suffered from famine, which even caused many deaths. In order to contrast this problem, the European countries involved in this conflict reacted in different ways regarding food policies and the effects showed different results. This topic will be treated by looking at three aspects:

-

the reduction of food availability which characterises all wars;

-

the evidence of hunger and deprivation on the civil population;

-

the propagandistic representation of a non-suffering Italy which can ‘peacefully’ face the the food emergency.

Workshop Subject: Sources show, with few exceptions, how wartime events and Italian government politics brought to a depriving situation with lack of food and highlight the terrible conditions of the civil population and their struggle in finding food. On the other hand, other types of documents show the official versions of the regime portraying Italy without sufferance and able to use particular methods and forms of survival. The comparison of these two representations, looking at the Italian situation but also keeping a European perspective, will be fundamental.

Workshop Goals: to show how conflict, in a total-war logic, totally transforms the civil population’s everyday life, even faraway from warfront areas.

Classes involved: classes 3e, scuola secondaria di primo grado (lower secondary school).

Duration: 4-6 hours

Prerequisites:

-

Basic knowledge of the happenings of the Second World War in Italy

-

Basic knowledge of European geography

-

Basic experience in the use of historical sources

Objectives: Gain competencies regarding:

-

decoding, analysing and distinguishing different types of sources and texts;

-

extracting information from any type of source or text;

-

recognising the topics and intentions of those who produced the documents;

-

identifying common elements and key words;

-

comparing by similarity and difference in order to make models and interpretations;

-

composing data and information through temporal, spatial, social and cultural interpretations;

-

building timelines, recognising the temporal order of narration;

-

acquiring lexical and conceptual tools regarding the historical discipline and using them appropriately;

-

listening, understanding and following others’ reasoning;

-

intentionally using a suitable lexicon for clear and authoritative speech.

Activity methodology and organisation

The workshop activity will be carried out in the classroom, organised into work groups and will include the following operations:

1. selecting certain documents from a simulated, specially-made archive based on the suggested themes;

2. questioning the documents depending on their different types (source critique, searching for clues, etc…);

3. developing a summary of the collected information starting from the link among the documents inserted in the workshop;

4. comparing each group’s results on the different analyses of the sources regarding the representation of the information. This task should be a preliminary step to the production of a historical project (written, oral, visual, etc…)

Sources

Documents and photos

- Mensa del popolo, 1944, Bologna (Archivio ANPI Bologna)

- Fila al mercato, 1944, Bologna (Archivio ANPI Bologna)

- Orto di guerra, 1943, Bologna (Archivio Istituto Parri)

Audio-visual documents

Quantitative data

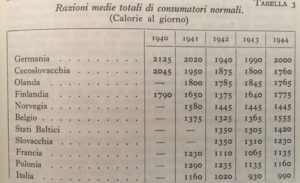

- Table 1: Average total rations Europe calories a day (1940-44) from the table: “Italian Encyclopedia Treccani”, Appendix II, 1938-1948, p. 219

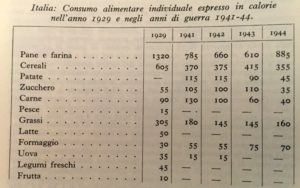

- Table 2: Individual food consumption expressed in calories in 1929 and during the war. Table from: “Italian Encyclopedia Treccani”

Memorialistic

“bread was all eaten straight away, both because there wasn’t much of it and because it tasted so bad that if it wasn’t eaten immediately it became so hard to put your teeth at risk. On the days when it wasn’t sold, bread was made at home with any scraps of flour you could find and without yeast because during the war, it had disappeared as well. […] Salt couldn’t be bought at the chemist’s or anywhere else. There was no salt. However, Venice was a lot luckier in this aspect as they had canals. People used to go to the nearest canal with the biggest pot owned to fill it up with water. once returned home, the pot would be put on the stove in order to evaporate the water for a few days so that a layer of salt would remain on the bottom of the pot.”

Testimonianza di Maria Rosalia Binetti, in Giulia Albanese – Marco Borghi (a cura di), Memoria resistente. La lotta partigiana a Venezia e provincia nel ricordo dei protagonisti, Iveser, Venezia, 2005, p.858

“1941

September, 25th

Oh, no! For god’s sake, not bread! Oil, butter, soap, flour and sugar have been rationed by a rationing card system: we are given a hundred grams of meat per week; we have totally been deprived of pasta, rice, cold cuts, tuna, canned meat, eggs […]; the carding system is in progress for potatoes, beans and even cheese which used to be our only resource; not to mention the suspension of the production of pastries, biscuits and so on; however up to now we still had bread! You could have largely enough of it by going to the baker’s in time and queuing for a while. If there is bread, people will not go hungry!

Maria Carazzolo, Più forte della paura. Diario di guerra e dopoguerra (1938-1947), Verona, 2007, pp.61-62

“For food we had our cow’s cheese and milk, our pork, omelettes made with just a few eggs because eggs were as precious as money, and so when we had to buy something in shops, we payed in eggs. […] The shopkeeper gave us some food in exchange for an egg, especially sugar, salt, rice and oil.”

Ricordi di nonna Speranza G., in Barbara Cercato-Amina Gabriele (a cura di), La Storia è nella Memoria. 1940-1945: ricordi e racconti, Trieste, 2004, p.17.

Here life keeps getting harder. Hardly anything is found at the market; producers are no longer bringing any food due to the prices imposed by the State because they think that they are not appropriate for the general cost of life and the current cost of goods. All the speculators and producers have decided they want to make lots of money and it seems like nothing can stop their desire to make more and more of it.

Letter sent from Florence on 10th June 1942, intercepted by the censorship.

Precettistica del tempo di guerra

Queueing discipline

Often forced to wait patiently ‘’lined up’’ in a queue in order to have a type of food or another and undergo the ration book system meant being very patient; a servile or sheep-like patience was not necessary but a conscientious patience which made us strongly endure the condition while thinking that all of this was nothing as these sacrifices were totally void compared to our men standing at the warfront. We lack love and respect towards them by complaining about these inconveniences. Most importantly, each of us must know how to stay in our place with military rigour. Those who go out of line, push or nudge others, take the rights of those who got there before us and totally fail and damage their civil and patriotic honesty.

Lunella De Seta, La cucina del tempo di guerra, Milano, Salani, 1942, p. 337.

Oil mix of oil and flaxseed oil

Where can we find this oil mix? Easy. You have to prepare it yourself with very little real, authentic olive oil, flaxseeds and a lot of water. […] Use 125 grams of oil, 25 grams of flaxseeds and less than a litre of water. Mix the three cold ingredients, stir them together with a spoonful of vinegar (also cold), a pinch of salt and a tad of saffron. Warm the mixture on the stove and let it boil for 20-25 minutes.L. De Seta, La cucina del tempo di guerra, Milano, Salani, 1942, p. 35.

PART TWO A possible development

Among numerous possibilities, let us look at an example of how to develop the proposed themes through the selection of some documents in the simulated archive. After selecting these, we built a workshop path which questions and looks for clues in the single sources – trying to link these with different types of documents – to build a sequence which allows thematisation and the historical narration of facts.

The workshop opens with a video which is useful in suggesting themes and issues.

From “Correva l’anno”, Rai1, 2005 (Archivio dell’Istituto Luce, Roma, 1940-1945);

The vision could be introduced by the teacher giving a few thoughts to the students or could be left to their free interpretation. It will be necessary to say that the video of the Istituto Luce has clear propagandistic intentions.

Its focused themes are:

-

the importance of bread and wheat. Mussolini was the author of “Preghiera al pane” (bread prayer) of which we can still read some of the verses. Bread became the symbol of the simplicity of consumption and of life, concept which the country at war wanted to portray.

-

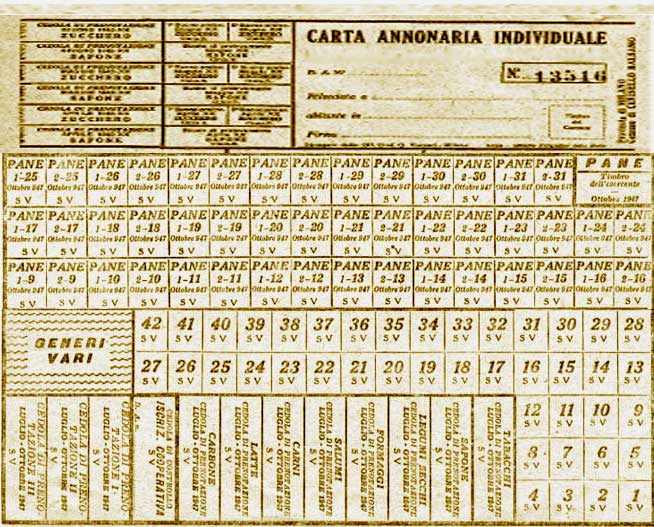

rationing and ration books (cards) and their effects on daily life. Buying goods through ration cards meant that the consumer could only receive a fixed daily amount. Those who supplied food cut out and put stamps on the cards once the daily portion was delivered to each person.

The video leads to several considerations that can become guide-questions for the students.

-

What could this strong attention towards wheat and bread mean? Does it suggest an image of a rich country?

-

Observe how the production of bread loaves is portrayed. What does this suggest?

-

Why does the food supplier cut out a part of the card?

-

How are women that go grocery shopping presented?

-

What does the fact that they appear competent and used to doing this it suggest?

Being a reconstructed reality, the film is able to introduce both the issues which the workshop intends to focus on. These include a climate of tight circumstances (in a normal situation it would not be necessary to have cards which record how much bread you are given) and the will to overcome the harsh situation through the construction of an optimistic narration which leads to supporting the population but also hiding the dramatic aspects that war can bring to daily life.

Memoirs confirm the fact that bread was the basic part of the diet for many people. As we can read below:

“bread was all eaten straight away, both because there wasn’t much of it and because it tasted so bad that if it wasn’t eaten immediately it became so hard to put your teeth at risk. On the days when it wasn’t sold, bread was made at home with any scraps of flour you could find and without yeast because during the war, it had disappeared as well. […] Salt couldn’t be bought at the chemist’s or anywhere else. There was no salt. However, Venice was a lot luckier in this aspect as they had canals. People used to go to the nearest canal with the biggest pot owned to fill it up with water. once returned home, the pot would be put on the stove in order to evaporate the water for a few days so that a layer of salt would remain on the bottom of the pot.”

Testimonianza di Maria Rosalia Binetti, in Giulia Albanese – Marco Borghi (a cura di), Memoria resistente. La lotta partigiana a Venezia e provincia nel ricordo dei protagonisti, Iveser, Venezia, 2005, p.858

“1941

September, 25th

Oh, no! For god’s sake, not bread! Oil, butter, soap, flour and sugar have been rationed by a rationing card system: we are given a hundred grams of meat per week; we have totally been deprived of pasta, rice, cold cuts, tuna, canned meat, eggs […]; the carding system is in progress for potatoes, beans and even cheese which used to be our only resource; not to mention the suspension of the production of pastries, biscuits and so on; however up to now we still had bread! You could have largely enough of it by going to the baker’s in time and queuing for a while. If there is bread, people will not go hungry!

Maria Carazzolo, Più forte della paura. Diario di guerra e dopoguerra (1938-1947), Verona, 2007, pp.61-62

All of the documents analysed up to now speak about rationing policies (see In-depth Information) and recall the use of ration books (see In-depth Information).

The analysis of one of these cards allows us to understand further details.

In-depth Information 1. Rationing

We usually speak about rationing when referring to natural disaster or war. This means that the administration imposes a limit on the availability of food or goods which are considered scarce in order to collect them and redistribute them according to determined criteria. In Italy, the norms regarding rationing came into force on the 2nd May 1940 through the Sezione Provinciale Alimenti (Sepral) institution, organisation which managed the stockpiles and food distribution. However, irregular distribution soon caused contraband and a black market which led to inflation (between 1940 and 1942 the cost of grocery shopping increased by 67%).

In-depth Information 2. Ration Books

The buying of the rationed food was controlled by the prefect through the use of a Ration Book (card). This was a nominal, bimestrial document that allowed people to reserve food or other goods at a selling point. It’s use left a mark in Italians’ lives from 1940 to 1949. The card was printed on different coloured paper depending on the age groups: green for children up to 8 years of age, light blue for teenagers from nine to eighteen and grey for adults. Each card showed the owner’s details which were written in black, permanent ink. The buyer had to show the card to the food supplier, usually after a long queue, and the top band of the card was cut and stamped. The date of the reservation and the collection of food were announced through posters and in newspapers.

The work group or class could be asked to analyse and describe the ration book in order to understand which types of food were given out.

The quantitative data, shown here with the Informa tool, helps us to understand how the quality of food declined throughout the period of conflict. Similar data can be looked at in class in order to build up similar infographic information. The quantitative tables help us to understand the European and Italian situation and show the slow but persistent reduction in daily calorie intake and the progressive extinction of the most common food types (especially fresh food).

The same data of Table 1 now visualized in a map

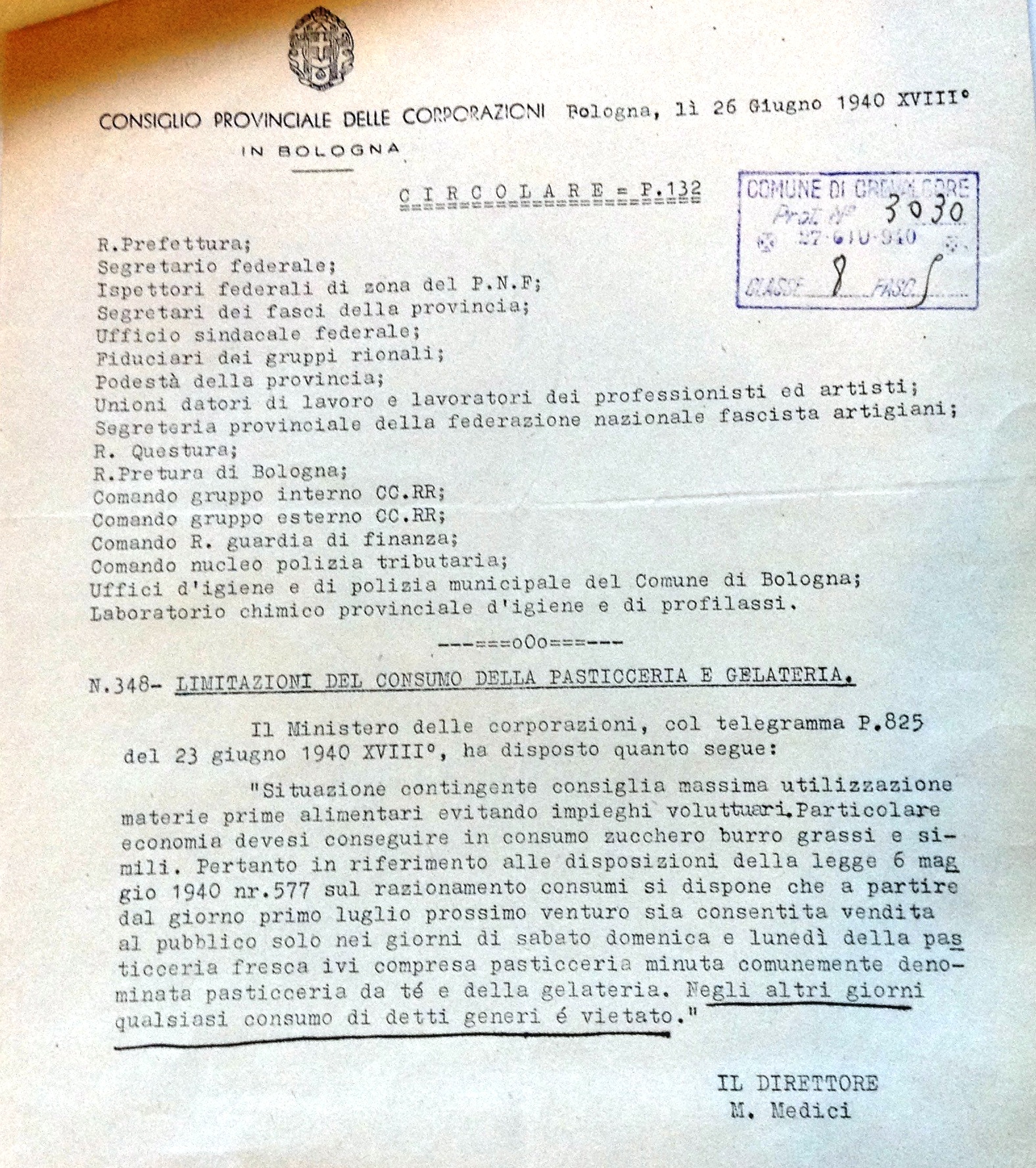

In Italy, newsletters about the limitations in the consumption of luxury goods were released just a few weeks after the beginning of conflict. Pastry and ice cream shops, as read about in the memoirs, became totally scarce. Flour, sugar and fats became rare and were not to be wasted for the production of foods that were not primarily essential.

This was only the beginning of a progressive worsening of dietary conditions. The details of this transformation can be summarised and seen through the making of a timeline which depicts the restrictive measures.

The stages of rationing politics in Italy

Shops were often out of food and it was common to have to wait for long periods of time before being able to enter into the shop to reserve or collect goods.

(Archivio ANPI Bologna)

This picture shows Bologna in 1944 and represents a situation so common that many old scrapbooks of the time mention it specifically. See the following example.

Queueing discipline

Often forced to wait patiently ‘’lined up’’ in a queue in order to have a type of food or another and undergo the ration book system meant being very patient; a servile or sheep-like patience was not necessary but a conscientious patience which made us strongly endure the condition while thinking that all of this was nothing as these sacrifices were totally void compared to our men standing at the warfront. We lack love and respect towards them by complaining about these inconveniences. Most importantly, each of us must know how to stay in our place with military rigour. Those who go out of line, push or nudge others, take the rights of those who got there before us and totally fail and damage their civil and patriotic honesty.

Lunella De Seta, La cucina del tempo di guerra, Milano, Salani, 1942, p. 337.

Some questions can help us understand a reality that can seem very distant from the one of today’s students:

- Observe the picture. What can you see? Are there any signs that highlight the war period? Do you see a particular war phase?

- Who is queuing?

- Does it seem like a quickly moving queue?

- In the extract taken from the scrapbook, what motivates the author to respect the rules?

- Why shouldn’t people complain of the difficulty?

- Are there any terms which suggest a propagandistic angle?

The situation was difficile but not the worse possible. As seen in the video below, the areas of military operations or where bombardments hit cities or towns the hardest were totally unrecognisable and shops were destroyed.

Some of the urban areas became similar to the countryside areas as the effects of war and destruction led to this. As seen through the diagrams, vegetables and fruit produced in the vegetable fields were taken away from the marketplace. The war interrupted the daily relationship between the city and the countryside that the supply of this food had created. The regime proposed and subsidised the self-production of vegetables on home balconies, bushes, green open-spaces and of wheat in public parks. The breeding of small animals such as chicken or rabbits was encouraged on terraces and in private gardens. This pictures shows a central area of Bologna set up as a vegetable garden. It is taken from a private archive with no propagandistic scope, differently form the two pictures that follow.

Orto di guerra a Bologna (Archivio Istituto Parri)

The two documents taken from the pages of a newspaper (“Il Resto del Carlino”) clearly show a propagandistic intent.

Some of the following questions can guide the analysis:

- In the first picture, the heading states that growing a vegetable garden during the war is a duty. What does this mean in your opinion?

- What does the comparison between these images and the picture which shows people queueing outside shops suggest? Do you think that the policies which pushed vegetable cultivation during the war helped the problem of hunger?

- Why was the main square of a medium-sized city, such as Bologna, set up as a place of wheat threshing? (this is referred to as an‘’exceptional event”).

- Look carefully at the public in the second picture. Does it look like it is made up of farmers or people in charge of agricultural work?

Some areas of Rome which were transformed into open-air vegetable gardens are shown in this video of the Istituto Luce.

Here too, as in the picture of the threshing in the square, the protagonists are citizens. Men and women wearing middle-class clothes working in the fields but showing very little familiarity with this type of work. The propagandistic angle is visible again: a detailed analysis of the images and how they are edited and assembled show revealing clues. Students could be proposed with two or three consecutive visions and asked to pay attention to certain details (a first vision could be dedicated to the description of the environmental context, a second one could be the observation of the protagonists and their clothes, a third one the actions carried out in the picture). These observations could then be put together in one file.

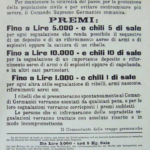

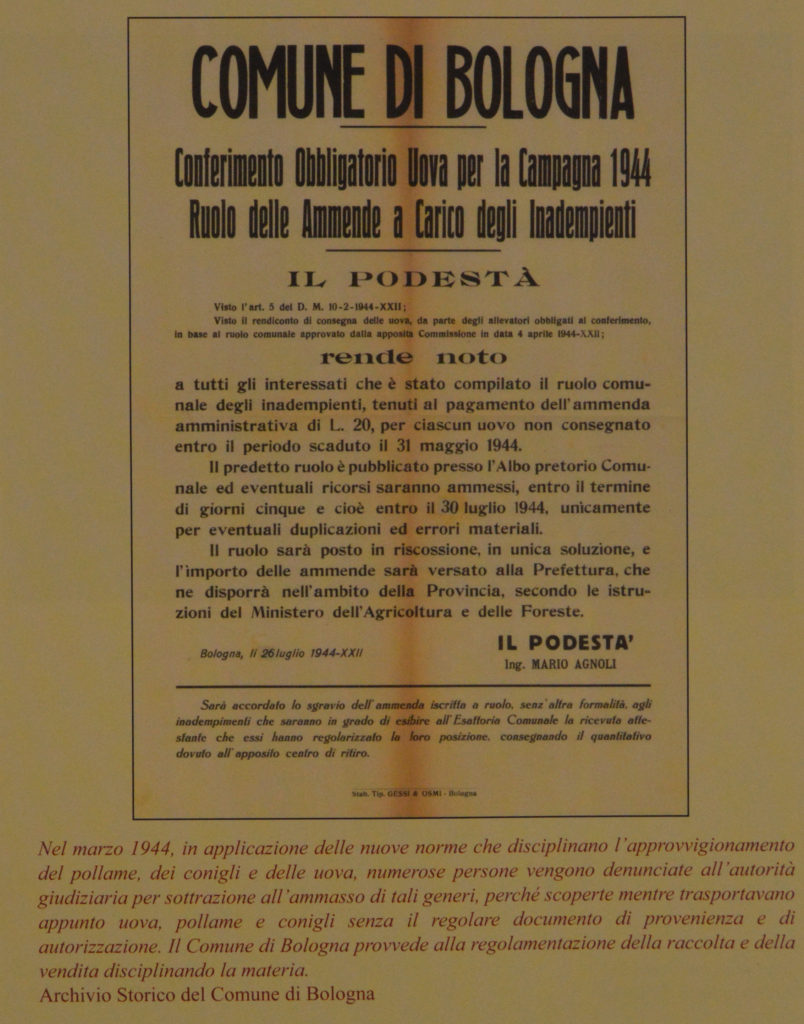

Another important measure taken to limit waste and the black market was the Stockpile policy (see In-depth Information) regarding agricultural products. The following document announces the policy regarding the egg stockpile policy.

Actually, eggs played a central role in the war market from the start, as we can see in the following memoir:

“For food we had our cow’s cheese and milk, our pork, omelettes made with just a few eggs because eggs were as precious as money, and so when we had to buy something in shops, we payed in eggs. […] The shopkeeper gave us some food in exchange for an egg, especially sugar, salt, rice and oil.”

Ricordi di nonna Speranza G., in Barbara Cercato-Amina Gabriele (a cura di), La Storia è nella Memoria. 1940-1945: ricordi e racconti, Trieste, 2004, p.17.

In- depth Information 3. Stockpile policy

Measure which imposed a limit on how much of certain products could be owned by the people. The stockpile policy forced producers to give the State a fixed amount of their production, sold at a price which was decided by law. In 1935, this voluntary measure was imposed on wheat and was then diffused during the Second World War until it included a large number of agricultural raw materials.

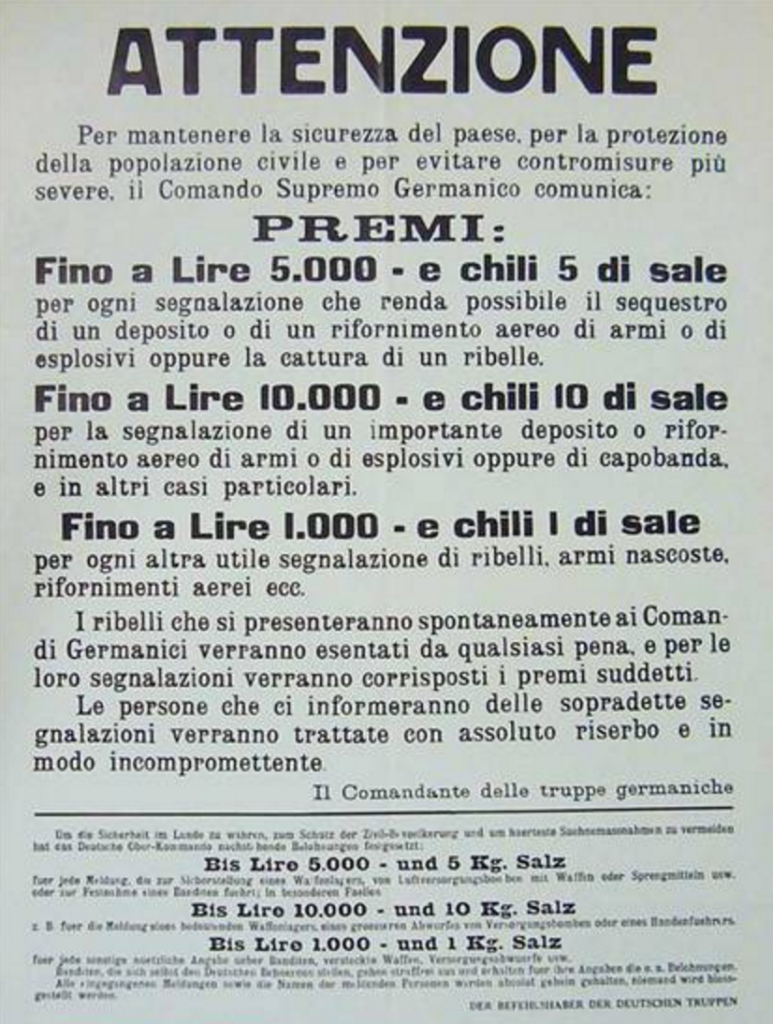

The rationing card system which involved certain goods of primary need showed how restrictive the regime was. This can be read about in other types of documents. Salt was so rare and precious that it became comparable to money. For example, in order to incentivate the reporting of partisans some law force chiefs offered money and salt as a reward.

During the last few months of the war, the people were less and less likely to provide for themselves. For this reason, soup kitchens were set up in many districts so that food was provided in exchange for a small amount of money.

La mensa del popolo (Archivio ANPI Bologna)

While a large majority of the population was suffering from hunger, a small minority was taking advantage of the situation to earn money. The black market (see In-depth Information) flourished and the authorities were not able to control it. See this memoir extract taken from a source below:

Here life keeps getting harder. Hardly anything is found at the market; producers are no longer bringing any food due to the prices imposed by the State because they think that they are not appropriate for the general cost of life and the current cost of goods. All the speculators and producers have decided they want to make lots of money and it seems like nothing can stop their desire to make more and more of it.

Letter sent from Florence on 10th June 1942, intercepted by the censorship.

The black market was highly diffused even if it later left very few traces. Those in charge of it made sure that its nature of forbidden and sanctioned activity was kept as confidential as possible. Here it is shown in a video clip taken from the film “Abbasso la miseria”.

In-depth Information 4. The black market

The black market refers to illegal commercial exchanges. This phenomenon was highly widespread during the Second World War and occurred differently in the North and South of the peninsula. In the North, the rationing and stockpile policies effectively regulated the market, in the Central-South area (especially in Rome and Naples) contraband purchases were more popular than those of the regular market. In Rome, the average amount payed for food in a family unit was 408 lire per month and reached 2,533 in September 1943 and 9,339 in September 1944. Only 4% of these figures included food bought through the rationing card system, 26% bought in the free, non-rationed market and 70% bought on the black market.

The spirit was very low and the atmosphere inconvenient, shown by the laconic war scrapbooks which reported recipes in order to use even the crumbs to save as much as possible on money and resources, as seen below:

Oil mix of oil and flaxseed oil

Where can we find this oil mix? Easy. You have to prepare it yourself with very little real, authentic olive oil, flaxseeds and a lot of water. […] Use 125 grams of oil, 25 grams of flaxseeds and less than a litre of water. Mix the three cold ingredients, stir them together with a spoonful of vinegar (also cold), a pinch of salt and a tad of saffron. Warm the mixture on the stove and let it boil for 20-25 minutes.L. De Seta, La cucina del tempo di guerra, Milano, Salani, 1942, p. 35.

It is interesting to notice how this recipe used to obtain watery oil from a boiling mixture of vegetable fat was proposed in 1942, a year before the 1943-1945 worse two-year period of conflict in Italy, hardest for survival.